In the Loop. My CLID has a contract out on me...

A post-phenomenological rethink inspried by life with a closed loop insulin pump.

Introduction

American Philosopher Don Ihde (1934-2024) coined the term postphenomenology in 1995. He aimed to move the philosophy of technology towards a deeper consideration of relations between humans and the technologies that we use to shape our world—and how many, in turn, shape us. He hoped to augment the experiential focus of Pragmatism using some of traditional phenomenology’s analytical tools (e.g. variational theory and multistability) and moving towards an ‘organism-environment’—rather than ‘subject-object’—perspective. As we’re seeing today, it was a way of shoehorning a more inter-disciplinary approach into technology studies.

Idhe saw philosophy working with sociology and psychology in the analysis of ‘technologies in practice’, side-stepping ontological and epistemological cul-de-sacs that had hampered traditional phenomenology. His ‘special move’ built on Hans Achterius’s empirical work in the philosophy of technology: edging away from the generalised consideration of technology as a discrete force ‘out-there’ and towards the particulars of everyday technologies that are forged praxically in the crucible of their intimate relations with our bodies, minds, senses and interactions (Ihde 2006).

Ihde’s framework still enriches the study of human-technology ‘co-constitution’ using four categories of relationship (I will come to these below).

Here, I aim to bring Ihde’s thinking to life by looking at a particular class of embodied medical technologies that use biofeedback loops to inform—and sometimes act upon—users. I’ve been using one for 12 years. It came as a liberating force into my life after 30 years as a self-jabbing Type1 diabetic: the insulin pump.

CLIDs - a deep body, multi-modal technology

My Closed Loop Insulin Delivery system (hereafter CLID) is a 24/7 attached ‘part of me’. It’s a technology, fundamental to the control of my endocrine system, metabolism and ultimately my moods and my ability to both survive and function ‘normally’.

I argue below that the complex nature of a CLID’s interactions with (what Helena De Preester has called) the ‘in-depth body’ (De Preester 2006) make it a multi-modal technology that warrants an extension of Ihde’s categorisation. I propose that a quasi-contractual relationship arises between CLIDs and diabetics who use them. I control it autonomously but it can also control me autonomously. It can even bypass me and seek relations with other people. It can take emergency action if it senses that I’m not able to. But all this only works if it and I agree to abide by a contract of engagement. Intrigued…? Well come under my skin for 10 minutes.

Contracts

A diabetic awarded an insurance pump by their Health provider (Alas, I have to pay for my own pump because I don’t want a steam-punk version offered by the health authority… although they do pay for all my consumables and insulin) must accept that this technology becomes part of them and requires their compliance and their permission to allow it to shift modes of relation, exercise agency and change its intentional direction. These shifts are cued dynamically— and sometimes autonomously. The language here is contractual. There is no AI in the pump but its set up in a way that we can only work together if I accept it has a special sort of agency.

Before I go too deep, let’s look at Ihde’s framework I hope to extend.

Ihde’s categories of technological relations

Surveying the rise of modern technologies, Ihde described the rise of technoscience. That is where technology aids and illuminates science, and vice versa. It is “the hybrid output of science and technology now bound into a compound unit” and he proposes that the postphenomenological approach is, in effect, a phenomenology of technics allowing us to “look at the spectrum and varieties of the human experience of technologies” (Idhe 2006). In Technology and the Lifeworld, Ihde illustrates said varieties with a day kicking off amid a stream of activities and decisions, all mediated by technologies that are barely noticed so deeply are they woven and embedded in his lifeworld (Ihde 1990). Thermostat, alarm clock, coffee machine. In his Peking Lectures, Idhe set out four categories of such relations:

Embodiment relations which include bodily ‘extensions’ and technologies that are incorporated into—or onto—the body and may ‘withdraw, becoming transparent as we experience directly through them without even noticing.

Hermeneutic relations where experience is mediated via the interpretation of say dials, gauges or other indicators. These relations are no longer analogous to everyday sensory experience as there is no direct experience of the phenomena that the technology reports on.

Alterity relations where we relate to technologies as “quasi-objects or even quasi-others”. These relations occur with technologies ranging from ATMs to humanoid robots where our interaction is with technology itself for its own sake.

Background relations which remain in the perceptual periphery; present but unnoticed until attention is drawn to them or needed by them. Examples include the humming of an air conditioning fan or the flashing LED of an untriggered burglar alarm.

(Ihde 2006)

Technologies may straddle two categories or move between them—for instance, the thermostat that functions imperceptibly in the background until hermeneutic interaction is prompted by cold weather (ibid).

Modern connected technologies present a more complex challenge. Rosenberger’s work on mobile phone interactions highlights their ability to ‘seize control’ over a user’s field of awareness during a call (or in modern times, Facetime and Whatsapp videos) (Rosenberger 2006). Smartphone users expect their mobile to span and move across categories. Their modal shiftiness glides by unnoted as we move between using the phone for calls, messages, games, alarms, video surveillance, movement tracking etc. The phone itself or other parties (i.e. callers or text messagers) can instigate these shifts. Importantly for this argument, new relationships don’t arise with each modal shift. We feel throughout that we are interacting with or through ‘our phone’ rather than with a current relational mode, be it embodied, hermeneutic, background or alterity. We accept (and expect!) that a smartphone functions as a multi-modal ‘remote control for life’. This indicates a special kind of intentionality that may direct ‘at’ anything that accepts remote interaction via GSM, Bluetooth or mobile data/IP.

If we accept Rosenburger’s view (I do) then Ihde’s categories become modes rather than instances of human-technology relations. And with this, deeper, darker challenges arise in his account of modal intentionality and agency, starkly illustrated by medical technologies that operate in deeply-incorporated—and occasionally autonomous—‘measure-respond’ biofeedback loops with those of us who rely on them.

Some might argue that these relations are what Peter-Paul Verbeek calls ‘cyborg intentionality’? (Verbeek 2008). I don’t think so, but let’s examine the concept first.

Verbeek’s Cyborg Intentionality

Verbeek introduces ‘fusion technologies’ into the postphenomenological analysis of human-technology relations to overlay different brands of intentionality onto Ihde’s relational descriptions. He argues that Ihde’s categories represent a spectrum of distances from the body. Hearing aids and spectacles are close enough to be embodied relations but some background relations sit huge distances away from the bodies they relate to (e.g. satellites).

Fusion technologies such as neuro- and cochlear-implants sit much closer than the nearest end of Ihde’s spectrum. With these, actual bodily fusion (eek!) takes place such that “no clear distinction can be made here between the human and the non-human elements” (ibid). This, Verbeek argues, is a cyborg relation that supercedes technologically mediated intentionality, creating a new ‘hybrid intentionality’ (Verbeek 2008). The deep fusion ushers in a new phenomenology where the fused hybrid can sample the external environment in novel ways. Rosenberger and Verbeek both talk of ‘bi-directional’ intentionality involving a reflexive interplay between human beings and technologies which ‘watch us as we watch them’ (Rosenberger/Verbeek 2015).

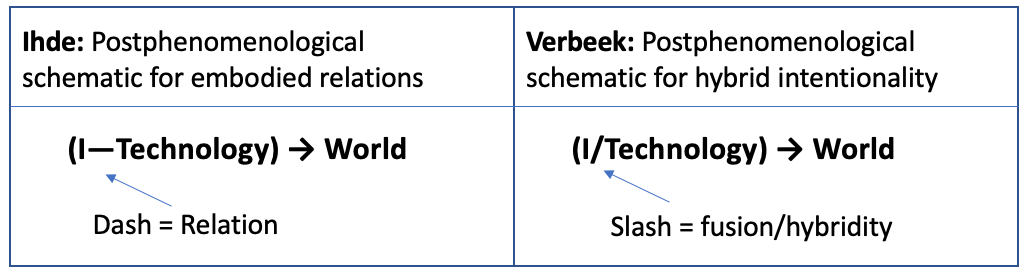

Adapting Ihde’s relational schematics, Verbeek supplements the dashes indicating relations and arrows intentionality with slashes (/) to indicate the fused basis of hybrid intentionality of, say, cochlear implants (see figure below) (Rosenberger/Verbeek 2015)

In biofeedback technologies, intentionality and sampling are not directed towards the external environment but towards the in-depth body world of the wearer. Putting ou r index and middle finger on our radial pulse and counting is a biofeedback technique using our own neatly built in technologies of tactile senation and counting! Biofeedback on the other hand measures phenomena from our inner world that are usually inaccessible otherwise.

Medical Biofeedback Technologies

The rise of wearable trackers and monitors of movement, heart rate, body temperature, ECG and other bodily metrics was a clear development in incorporated technologies. They monitor our activities and biomarkers of the body but usually remain withdrawn until we review and interpret them. Others can move from transparency into hermeneutic warning or action states under certain conditions. People warned by their cardiologists not to exceed certain threshold heart (HR) rates will wear HR trackers designed to interrupt them with audible and visual warnings if such thresholds are passed and to disrupt their behaviour. A hermeneutic imperative usurps the normally transparent function of such technologies. There is no ‘breakdown’ in Heidegger’s sense: the technology hasn’t broken or changed. Rather a modal shift has enacted the implicit contract of cooperation and permissions that user and their technology undertake at the outset. In blunt terms for some cardiac patient that contract states ‘engage or risk dying’. The user may not like being monitored by may also realise it's entirely necessary. Think of an annoying flatmate who wakes you when the kitchen is on fire.

HR and activity watches are embodied-but-detachable technologies. They are incorporated in the sense that we take a ‘technology, object or habit’ into our body image or schema. Meurice Merleau-Ponty’s example of a feather in a cap and the blind person’s cane are low-tech examples of such incorporation. The feather is pre-reflectively taken into account when navigating a low doorway and the cane with time and experience becomes transparent for the blind person in its incorporation (Merleau-Ponty 1962).

The very sci-fi sounding step of Implantation takes this an intrusive-but-necessary step further by incorporating technologies into the body. Ihde discusses stents, pacemakers and tooth crowns (Ihde 2019). Now, we have multi-focal intraocular lens replacements (I have two of these too!!!) and cochlear implants raise the bar of interactive fusion. Stents, pacemakers, implanted slow release drug capsules are transparent but free of hermeneutic requirements (unless they malfunction). Other technologies shift modes depending on user or biofeedback inputs. A notable (and fantastic) modern example is bladder control via Sacral Nerve Stimulation (SNS) where a permanently implanted device near the sacral nerve is controlled by an external device to facilitate urination.

For diabetics like me, CLID systems go even further interacting bi-directionally with the ‘in-depth body’—the sub-strata of endocranial and visceral functions that are not part of our body image or body schema (indeed we have no awareness or knowledge of their existence or function except when they exercise a causal effect on our perceptible body (De Preester 2006)). When the in-depth body is disrupted this threatens homeostasis and sometimes the entire body and brain’s ability to function.

Closed loop insulin delivery systems

Without a functioning pancreas, humans can’t survive more than weeks at most. Insulin controls our blood glucose levels (hereafter BG) metabolising consumed carbohydrate into enzymes that the body can use as energy. Thus, an unmedicated Type 1 diabetic (non-functioning pancreas) starves on a full diet; their BG rises unchecked causing weight loss, unquenchable thirst from osmotic failure, coma and eventually death. Type 1 diabetics require injected insulin therapy to manually control BG and metabolism.

CLIDs developed since 2010, form a system partially isomorphic to a ‘normal’ pancreas. A continuous blood glucose monitoring sensor (hereafter CGM) provides data to an insulin pump attached 24/7 that delivers insulin directly into the body using a cannula inserted 1cm into subcutaneous fat. The CGM is inserted via a similar cannula, sampling glucose in interstitial fluids every two minutes. CGM data combines with carbohydrate information that the user inputs manually when they know a meal with carbs is approaching. A rough CHO grammage is input manually to the pump by the user and an appropriate insulin response is calculated based on the pump’s computational model of human insulin therapy. The system seeks to maintain BG levels in an ‘acceptable’ range to prevent short term disruption to brain function caused by low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) and long term nerve and vascular damage from prolonged excessive blood sugar levels (hyperglycemia).

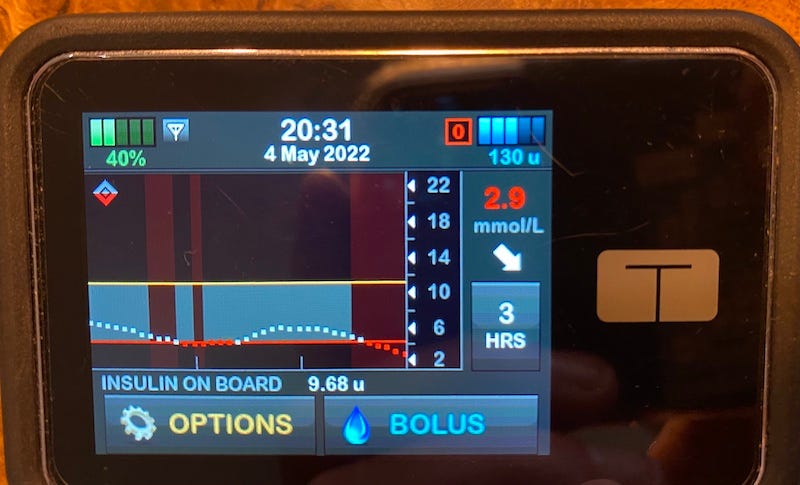

Closed loop systems are complex in their incorporation, interpretation and agency over the user. A CLID is an intimately embodied (but detachable) technology. It pierces the skin and enters the body but also includes an external device with an insulin reservoir and a screen displaying metabolic biomarkers such as BG, BG direction, insulin ‘on board’ (see photos below). All such metrics are accessible to non-users only via medical procedures. Some are for information only; others require—and occasionally demand—interpretation and action. For my argument, the combination of the pump’s computational model and the ‘contract’ the user makes with this technology allows it to control the endocrine system actively, and sometimes autonomously. It is the foundation of the CLID’s ability to deliver homeostatic balance in the absence of a functioning pancreas. It controls the ‘in-depth’ body which in turn controls our facility for normal mental functioning, perception, cognition, motricity, mood, emotional regulation and ultimately survival. At times, a CLID prompts its host’s interaction; at others, it takes control in ways that they cannot override unless they tear the technology from themselves and discard it. Users are often not even conscious of these autonomous actions. My pump often ‘takes over’ functions of my in-depth body without letting me know. In ‘user asleep’ mode, it is actively programmed to exercise control without input or notification wherever possible.

The CLID user is also required to maintain the system’s needs: insulin reservoir refills, infusion point changes, battery recharges, cleaning etc. Unlike Heidegger’s broken hammer, a breakdown does not give a wearer the luxury of observing the ‘present-at-hand’ pump as a scientific object of scrutiny (Ihde 2006). Rather, within 30 minutes, the body and mind may begin to lose their usual facility—including the ability to interact with the broken system. This intimate and reciprocal link is again indicative of a mutually binding contract between system and user: “you watch me, I’ll watch you…”. After adoption, the fates of user and pump are conjoined:: both must look after each other or both will cease to function.

The CLID ‘contract’ of agency and bodily ownership

Within a ‘normal’ BG range of 4.8mmol/l to 10mmol/l, human perception and cognition will—other things being equal—also be normal. Below BG levels of 4.5mmol/l, humans enter hypoglycemia. Excess insulin supplied by a CLID on account of say an inaccurate carbohydrate assessment, exercise (or a diet Coke served instead of a regular Coke!) metabolises the brain’s direct glucose supply into enzymes that it cannot use. This progressively and adversely affects the diabetic’s mood, perception and clarity of thought. As hypoglycemia deepens one may lose sensation in the legs or arms and become shambling, confused and disorientated. Perceptual fields lose coherence significantly below 3.8mmol/l and below 3mmol/l, one’s ability to resolve the visual field into differentiated objects may break down completely leaving hypoglycaemic diabetics in a visual ‘mush’.

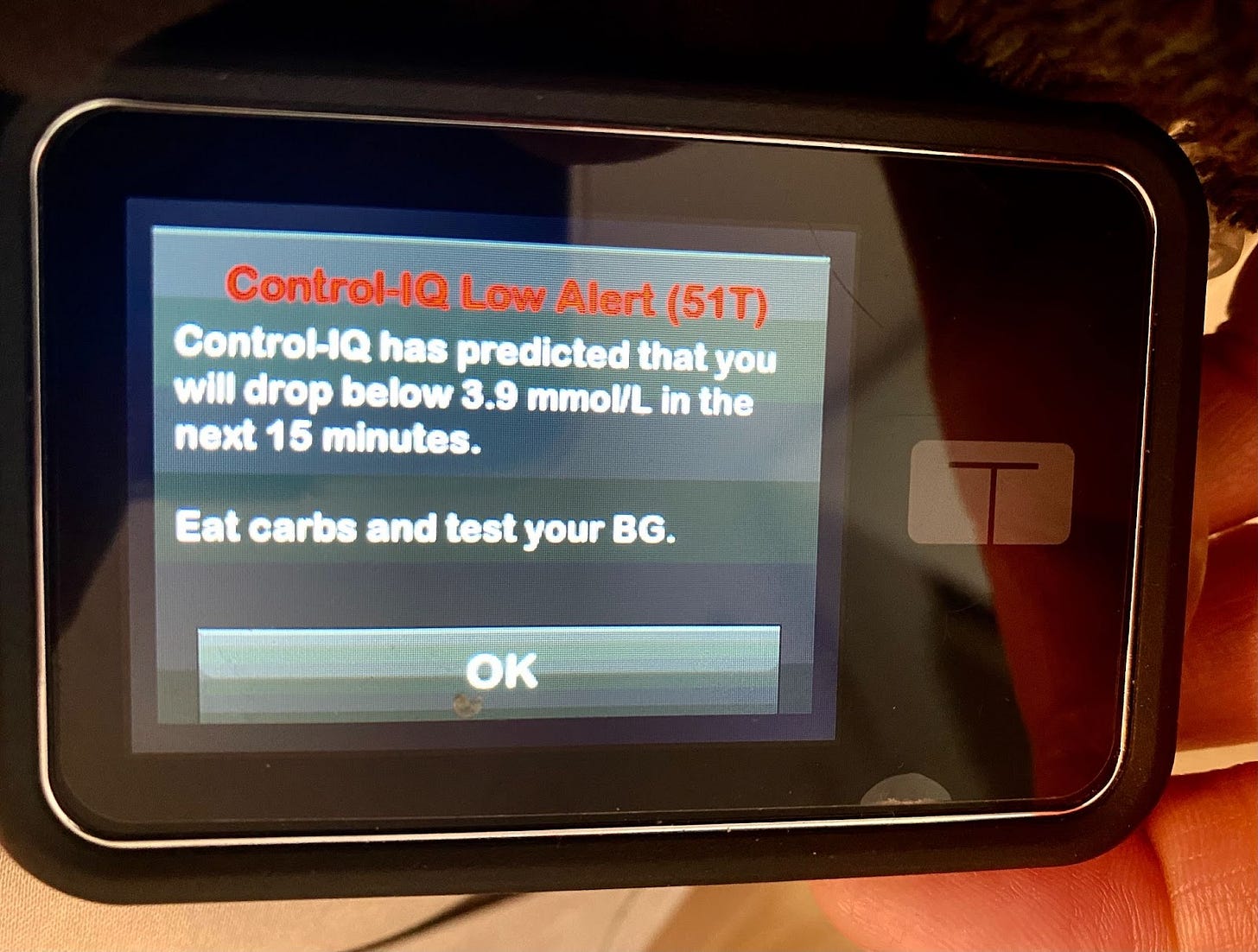

As the CGM detects a dangerous fall or rise in BG levels, it changes its mode and relationship with the user. It progressively, cumulatively and with increasing degrees of autonomy makes changes to the in-depth body (ie shutting off or boosting insulin delivery) and, when hypoglycaemia is confirmed, it escalates increasingly vigorous attempts to solicit confirmatory interactions. The CLID will vibrate and beep periodic warnings that cannot be disabled. The diabetic must respond by pressing a pattern of touch screen keys to demonstrate their ability to coordinate their movement. They must also acknowledge that they are in danger and going to consume carbs immediately (see below). If the user complies and BG rises again above 5mmol/l, the tirade ceases; if not, the volume and repetition frequency of the beeps and warnings rises with the express intention of attracting the attention of others than the user.

The autonomous nag of a CLID kicking in

The CLID thus moves independently between three of Ihde’s categories (embodied, hermeneutic, alterity). It may withdraw for long periods when BG is stable and in range. At these times, it remains hermeneutic allowing the wearer at a glance to read and interpret key metrics of metabolic function (see photo 2) but solicits no interaction. However, as in the example above, when BG drops or rises dangerously, its modes change and with them its phenomenology. In warning states, the CLID can feel scalding, angry and demanding to the user—petulant even. Finally, as it takes full autonomous control, it gains the alterity of a quasi-other, demanding first the attention and compliance of its wearer. If this is not sufficiently forthcoming, it shifts modes again and autonomously attempts to establish a hermeneutic relationship with others. Family or even public bystanders will eventually be drawn by loud warning sounds, locate the pump, read its messages and perhaps dial for an ambulance. This is not a fusion in Verbeek’s sense: the system establishes an ‘otherness’ and reaches out to the world independent of its user, wearer, patient.

Photo 2

CLID also presents challenges to De Preester’s analysis of the phenomenology of technological incorporation (that itself challenges Ihde’s classification where relative transparency is a distinguishing feature). She argues that the withdrawal of a much-used tool or the transparency of spectacles as they extend our sensory capabilities does not signify incorporation. Rather, she identifies incorporation with “bodily ownership” rather than the degree of prosthesis or implantations (De Preester 2011). With CLID, two 1cm subcutaneous cannulas are the extent of its tiny and temporary implantations, yet the bodily incorporation and phenomenology thereof is further reaching than most deeply implanted, “bodily owned” technology. The CLID measures what we can’t measure and acts as we can’t act to maintain homeostasis. In the final escalation of its alterity mode it becomes an externally directed alarm drawing attention to its stricken other. It breaks away from a closed, private feedback system to become an open one. A deeper alterity is hard-wired into the CLID’s computational model for emergencies.

Categorising CLID

Kirk Besmer’s insightful analysis of Cochlear Implants (CI) also challenges the applicability of Ihde’s categorisation where the quasi-restoration of a lost perceptual capability is made using a system that mixes fused and external technologies. With CI a unique ‘translation’ of auditory information occurs that requires months (sometimes years) of hermeneutic habituation to allow the user to near (but often never reach) the transparency of normal hearing. He thus concludes that CIs involve a “mix of embodied and hermeneutic relations but fully exemplifying neither…” (Besmer 2012). The same is true of CLIDs but the dramatic modal and phenomenological shifts they can make in response to biofeedback make a new categorisation necessary.

Unlike CI, CLIDs do not aid perception but underpin the biochemistry necessary for all perception, cognition and functioning. Also, unlike prostheses, IOLR, cochlear implants, pacemakers or bladder stimulators, CLIDs deliver an externally reservoired enzyme into the blood. They then sample the same blood to check the effect of this therapy.

This bidirectional nature that undertakes measurement/ infusion/control while retaining the agency to withdraw from the user, engage with them, or engage with other people in alterity mode deserves—I argue—a new category.

Rosenberger and Verbeek note that by taking a postphenomenological first person perspective to human-technology relations we can study not their ‘separateness’ but their ‘distinction’. When technology takes an active mediating role in our relations with the world then “Agency… is not an exclusively human property anymore: it takes shape in complicated interactions between human and nonhuman entities”. (Rosenberger/Verbeek 2015)

Conclusion

Don Ihde’s four categories of human-technology relations offer a useful framework for analysis of human-technology relations. However, I have argued here that some medical devices that interact bi-directionally present a significant challenge to his original postphenomenological account of technology.

CLIDs blur—and move autonomously between—the dividing lines of embodied, hermeneutic and alterity relations in a way that are blurred particularly by CLIDs. They enter the body but also remain largely external; they measure the biochemistry of the in-depth body and respond by administering a life-sustaining enzyme with or without prompting the user. Further, a CLID can (and will) exercise agency in moving out of transparent and withdrawn embodiment; through a quiet cooperatively hermeneutic mode; into a solicitously active hermeneutic mode; and finally into aggressively disembodied alterity directing itself insistently towards the outside world to assist its non-compliant diabetic user. At this stage, however, the user is not a ‘user’ but an ‘other’ that the system seeks to maintain while it takes control of soliciting external help.

This is how the CLID is designed, to act and respond to best protect its diabetic host.

I have argued that a new type of human-technology relation is thus in play; one perhaps best described as contractual. The multimodality and agency inherent in CLID operation require an agreement of mutual compliance in recognition that the human party is more likely to ‘fail’ than the technology party. The diabetic agrees to comply with and maintain the CLID but must also agree that she relinquishes both agency and control of her body to it in the event of non-compliance. With such devices, at any point both the technological and phenomenological relations with users may thus change dramatically and autonomously—but still in accordance with the implied contract of permitted behaviours. Philosophically CLIDs offers fertile ground to re-analyse classifications of intentionality, embodiment, incorporation and agency. While Ihde’s account remains useful, its classifications do not sit well with biofeedback technologies where relationships can shift dynamically.